Skift Take

As in the U.S., Chinese delivery services depend on two things that aren't sustainable: outside money and a labor pool that's too tenuous to be stable.

— Jason Clampet

Life in China’s largest cities can be very cozy. Air quality is getting better, and with a few swipes on your phone, a bubble tea or a spicy hot pot can be delivered in half an hour. The convenience is hard to beat.

Meituan Dianping’s $4.2 billion Hong Kong IPO last month shows that food delivery is now big business. The company, which is backed by Tencent Holdings Ltd., has burned through $3.4 billion of cash since 2015. That hasn’t stopped investors from rewarding it with a $40 billion valuation – even after the stock declined about 17 percent since its debut last month.

Underpinning Meituan’s success is what the company calls “abundant labor supply.” The cost of paying workers for each food order is about $1, or 20 percent of the expense incurred by delivery services in the U.S. An average order takes about 35 minutes, versus more than an hour in America.

For that, China’s urban consumers can thank the army of rural migrants who have crowded into cities in search of work. A deep pool of more than 280 million such workers exists to service the needs of middle-class city dwellers, enabling fast e-commerce and offline-to-online businesses.

But don’t take them for granted. Soon, there may be no cheap labor left in China’s large cities.

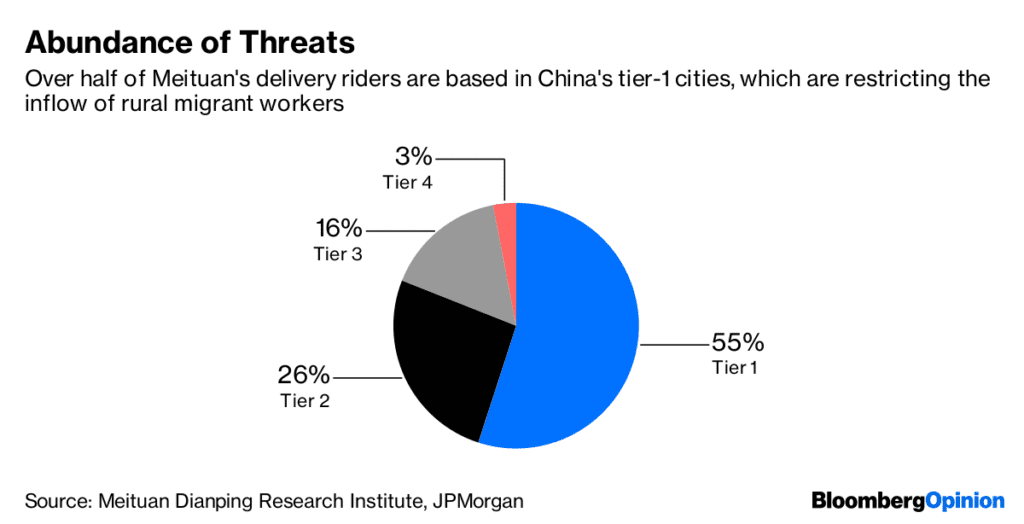

To fight pollution and traffic jams, mega-cities have started to restrict and even kick out migrant workers. Beijing plans to cap its population at 23 million in 2020, only 1.3 million more than its current size. Meanwhile, Shanghai has a target of 25 million by 2035, leaving room for only 800,000 newcomers. Meituan, which is battling Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. for food delivery customers, alone deploys more than half a million of delivery riders daily, over half of whom are based in the four tier-1 cities of Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen and Guangzhou.

Check out what it takes to get a city hukou, the equivalent of a permanent residency permit. What major centers such as Shanghai want are educated professionals, not neighborhood delivery guys. No wonder that only about 9 million migrant workers received urban hukou over the past five years. Without one, migrant families are denied access to public healthcare and schools.

Labor cost per delivery is expected to remain at around 7 yuan ($1) per delivery, Meituan said in its prospectus, quoting an iResearch report. That means profitability will need to come from “higher order density” – in other words, building a network compact enough that riders don’t need to go so far. Delivery workers are paid based on the distance they travel.

Even JPMorgan Chase & Co., which has a HK$90 price target on Meituan stock – implying a 60 percent upside – acknowledges that the company needs to focus on top-line sales to make money on food deliveries.

Meanwhile, turnover among riders can be high, because delivery is hard work. Meituan’s “super brain” real-time intelligent dispatch system can track a worker’s efficiency to seconds. All that stress is rewarded with only 3 to 7 yuan per order, according to my channel checks in Shanghai.

This is what a 50-year-old migrant worker’s life looks like there. Wang starts his day as a city janitor at 4 a.m., finishes at noon to join Meituan’s army of delivery riders for the lunch rush hours, and takes a two-hour break in the afternoon so as to be ready for a 5.30 p.m. to 10 p.m. dinner shift.

The Meituan gig pays better, says Wang, but his full-time janitor job gives him social security benefits. In Shanghai, employers are required to contribute 20 percent of a full-time worker’s salary to a pension pool and another 9.5 percent for medical coverage.

Last year, Meituan outsourced about 40 percent of its deliveries, with the rest handled by in-house employees. The company can save 2,000 yuan to 3,000 yuan per month on each part-time rider, according to a February survey from Meituan Dianping Research Institute.

Not surprisingly, many migrants plan to return home eventually. With savings from their city jobs – anecdotally, they make 7,000 to 10,000 yuan a month – along with cash settlements received from Beijing’s shanty-town development projects, they could build a better life back home.

Convenience always comes at a cost. Your bubble tea may not be as cheap in future.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.

This article was written by Shuli Ren from Bloomberg and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to [email protected].

![]()