Skift Take

The company wants to reduce delivery-related accidents, and lessen the burden of ongoing labor shortages in South Korea. That's fancy talk for robots taking over jobs humans do not want to do.

— Danni Santana

Soon in Seoul’s near future, citizens will be able to order jajangmyeon Chinese-Korean noodles, buy cold medicine and shop for magazines at home — and have them delivered by a robot in half an hour.

Kim Bong-jin, founder of South Korea’s biggest food-delivery app, is betting that autonomous gadgets the size of a small cooler will help his Baedal Minjok delivery service keep a grip on a market swarming with new entrants. The goal is to cut costs, reduce delivery-related accidents and cope with a labor shortage in one of the world’s fastest-aging nations.

This isn’t just an experiment for Kim, 42. His Dilly robots will start deliveries within three years. Woowa Brothers Corp., the company behind Baedal Minjok, raised $320 million from Hillhouse Capital, Sequoia Capital and GIC in December to help develop a prototype that’s set to roll out later this year. The goal is to tap into a global service robotics market projected to almost triple to $29.8 billion by 2023, according to MarketsandMarkets Research Private Ltd.

“We’ve proven that we can make money, so we would rather seize on the moment for more aggressive investment,” Kim said. “We have to change and experiment all the time.”

Valued at 3 trillion won ($2.7 billion), Kim’s startup currently handles about 28 million orders a month. Getting deliveries to people in the nation of 51 million is no easy task. First, Kim’s Dillys have to be able to navigate in urban landscapes dominated by tall residential buildings. He’s found a solution by partnering with a local manufacturer that would let elevators talk with the delivery robots.

The goal is to win over potential customers like Lee Dong-woo, who orders food at home at least once a week, getting everything from fried chicken and rice noodles to raw beef delivered to the door.

“I wouldn’t mind robots getting my orders at all,” said the 39-year-old Seoul office worker. “In fact, I’d like it more because I wouldn’t have to deal with sometimes unpleasant deliverymen.”

Kim has been recruiting an army of robotics engineers and working with Sunnyvale, California-based Bear Robotics Inc., which has been developing devices that deliver dishes to customers’ tables in restaurants. Kim thinks his Dilly robots will eventually be able to handle simple errands, including tasks such as throwing out garbage or delivering a home-made lunch.

“There’s a growing trend of using robots to do things that human beings do not want to do,” said Jing Bing Zhang, an analyst at IDC. “There are still a lot of technical challenges that need to be overcome. Especially in urban areas like Singapore, Shanghai and Seoul, there’ll be some safety concerns, whether they will be hit by other vehicles or will hit people.”

Kim is meeting some early resistance from people who dread the idea of robots roaming inside their apartment complexes. Critics say the Dilly robots would scare children and make their real estate less attractive.

“Some residents may still prefer humans, because they aren’t used to dealing with machines for payments and other services,” said Jin Se-taek, who represents an association of about 1,100 households at an apartment complex in Seongnam, south of Seoul. “We’d have to put it to a vote if we ever planned to allow robots in.”

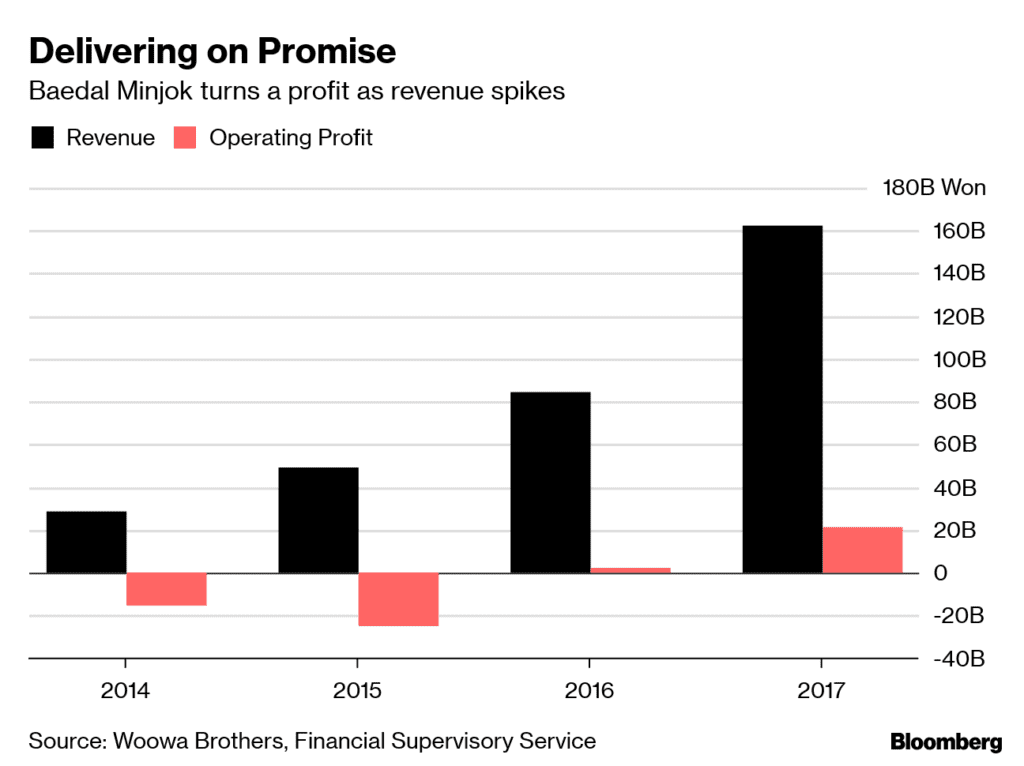

Kim has overcome setbacks before. In 2015, he was running out of cash, with just enough money at one point to pay salaries for another month after accepting demands from local restaurants to cut commission fees to zero percent. The decision drew kudos from the public and more users and businesses to the app, subsequently increasing advertisement revenue enough to offset the earlier loss and allow Woowa Brothers to turn a profit the following year.

Kim, who started out as a web designer at South Korean internet company Naver Corp., said he’s more willing to take risks because he doesn’t have a diploma from a top university or a resume that includes a name like Samsung or Google. Even though his company is one of South Korea’s six unicorns, according to CB Insights, Kim doesn’t believe in making people work longer than they have to. Kim restricts his workers from laboring more than 35 hours a week, five hours less than most companies in South Korea. So far, he’s satisfied with the increase in productivity.

“We didn’t introduce this so we could slack off,” Kim said. “My goal was to create a workplace where we could concentrate better. We should never stop thinking about how we can change the way we work so we change the way we live.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.

This article was written by Sam Kim from Bloomberg and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to [email protected].