Skift Take

This is a feel-good approach to what is a complicated challenge: Many seniors in the U.S. can't support themselves on their retirement. Restaurants are able to both provide help and take advantage of these problems.

— Jason Clampet

The sullen teenager grinding through a restaurant shift after school was once a pop culture cliche—as American as curly fries.

Nowadays, Brad Hamilton, the teen played by Judge Reinhold in “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” would probably be too young to work at the fictional Captain Hook Fish and Chips. That’s because senior citizens are taking his place—donning polyester, flipping patties and taking orders.

Fast-food chains are recruiting in senior centers and churches. They’re placing want ads on the website of AARP, an advocacy group for Americans over 50. Recruiters say older workers have soft skills—a friendly demeanor, punctuality—that their younger cohorts sometimes lack.

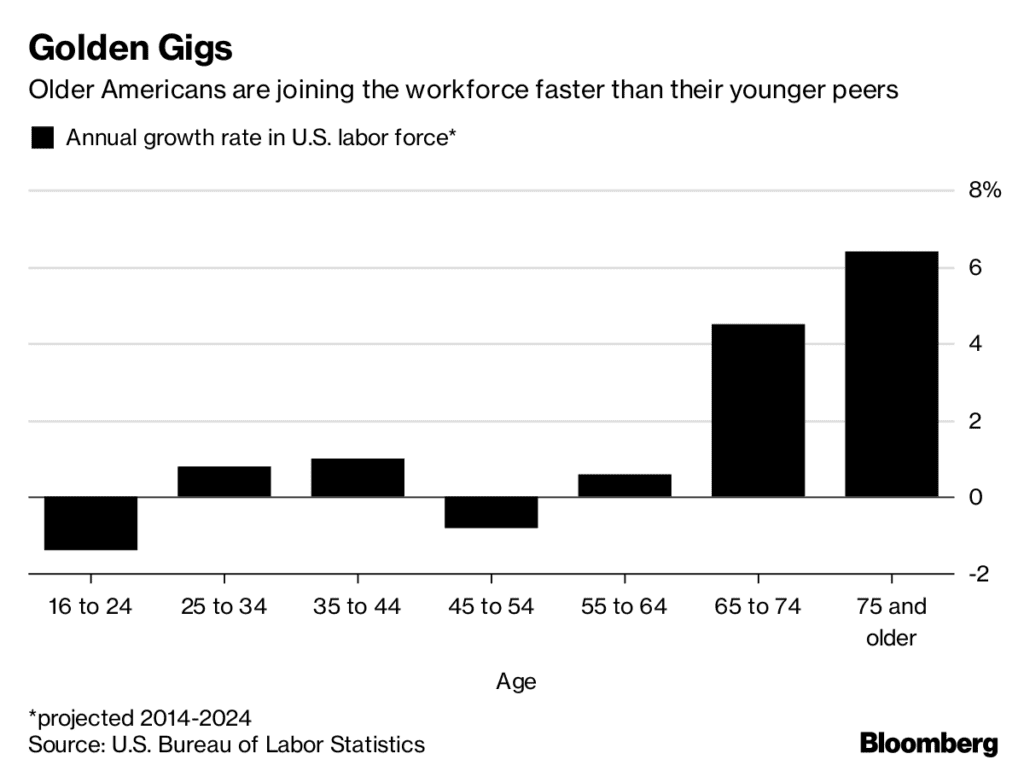

Two powerful trends are at work: a labor shortage amid the tightest job market in almost five decades, and the propensity for longer-living Americans to keep working—even part-time—to supplement often-meager retirement savings. Between 2014 and 2024, the number of working Americans aged 65 to 74 is expected to grow 4.5 percent, while those aged 16 to 24 is expected to shrink 1.4 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Stevenson Williams, 63, manages a Church’s Chicken in North Charleston, South Carolina. He’s in charge of 13 employees, having worked his way up from a cleaning and dishwashing job he started about four years ago and sometimes works as many as 70 hours a week when it’s busy. Williams is a retired construction worker and had never worked at a restaurant before, but was bored staying at home.

“It’s fun for a while, not getting up, not having to punch a clock, not having to get out of bed and grind every day,” he says. “But after working all your life, sitting around got old. There’s only so many trips to Walmart you can take. I just enjoy Church’s Chicken. I enjoy the atmosphere, I enjoy the people.”

Hiring seniors is a good deal for fast-food chains. They get years of experience for the same wages—an industry median of $9.81 an hour last year, according to the BLS—they would pay someone decades younger. This is a considerable benefit in an industry under pressure from rising transportation and raw material costs.

James Gray from Calibrate Coaching says older people are also a good deal financially because they aren’t always looking to move up and earn more.

They’re not “necessarily looking for a VP or an executive position or looking to make a ton of money,” he says.

Seniors typically have more developed social skills than kids who grew up online and often would rather not be bothered with real-world interactions. At Church’s Chicken, Williams coaches his younger co-workers on the niceties of workplace decorum. “A lot of times with the younger kids now, they can be very disrespectful,” he says. “So you have to coach them and tell them this is your job, this is not the street.”

AARP has become a veritable recruiting hub for the industry. In June, American Blue Ribbon Holdings LLC, which owns several casual dining chains, paid $3,500 to list hourly and management jobs on the non-profit’s website and hired five people for its Bakers Square and Village Inn dining brands. Bob Evans, a 500-plus-store sit-down chain that serves pot roast, biscuits and other homey fare, also recently advertised with AARP. Older hires typically work as hosts who seat customers and are “a nice fit with our brand,” says John Carothers, senior vice president of human resources.

Honey Baked Ham Co. is looking to churches and senior homes to help fill its 12,000 seasonal jobs for Thanksgiving and Christmas this year. The glazed-ham seller, which has more than 400 domestic locations, says older Americans are a key part of its staff, especially amid the labor crunch.

Toni Vartanian-Heifner, a 67-year-old former teacher, works part-time at a Honey Baked Ham restaurant in the St. Louis suburb of Kirkwood, Missouri. She often walks to work for four- or five-hour shifts that start at 7 a.m. She makes only about $10 an hour but gets a 50 percent discount on food.

Vartanian-Heifner is gearing up for the holiday season. “I enjoy the social part of it,” she says. “I think I’m going to work for at least five more years.”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.

This article was written by Leslie Patton from Bloomberg and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to [email protected].

![]()