Skift Take

Yes, the price of menu items has gone up over the last decade, but so too have the costs associated with buying food and paying workers. Those are the breaks.

— Danni Santana

Dollar cheeseburgers and discount nuggets are getting Americans in the door at their favorite fast-food joints, but the savings end there.

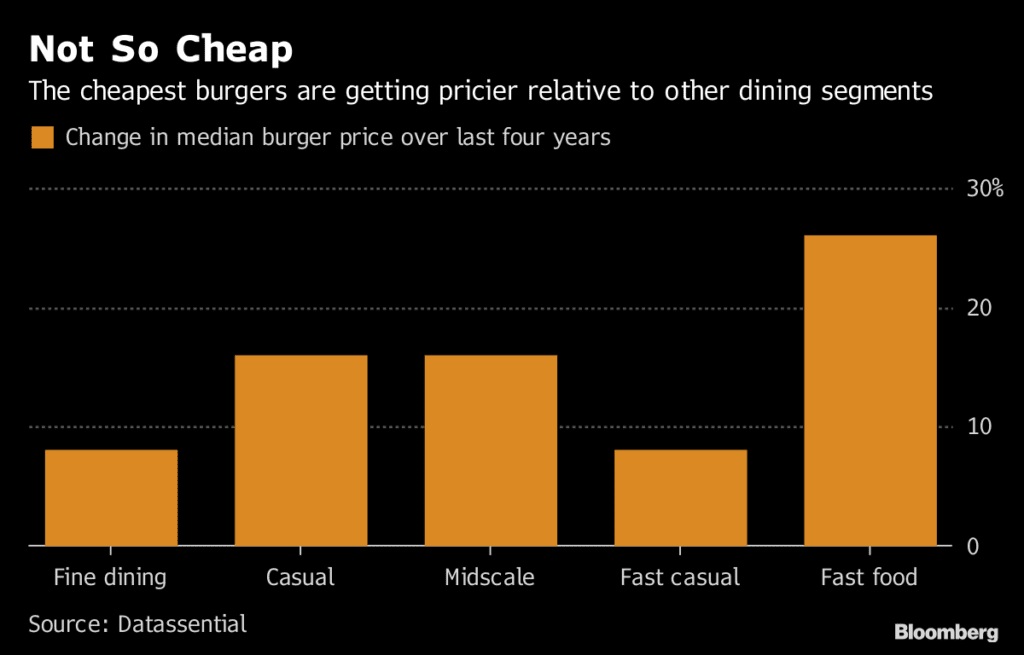

Even as the recent fast-food discount wars rage on, with Burger King advertising 10 chicken nuggets for $1 and Pizza Hut offering $5 pies, fast-food items that don’t make it onto value menus are actually climbing in price. Median fast-food hamburger prices have jumped 54 percent over the last decade to about $6.95, according to menu researcher Datassential. Chicken sandwiches are up 27 percent. Both surpass overall U.S. price inflation during that same time.

“It’s expensive to eat out — period,” said Bob Goldin, partner at food-service consultant Pentallect Inc. “Restaurant pricing is starting to be an inhibitor to the industry for growth.”

In Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood, a cheesy bean and rice burrito is just $1 at Taco Bell, but a Grilled Stuft Burrito is more than $5, and a steak taco is more expensive than at local Mexican restaurants nearby. Prices often vary by city and state, but the trend of more low and high-priced items with less middle ground seems to be expanding.

McDonald’s Corp., the world’s biggest restaurant chain, recently started touting a $6 meal including a burger, fries, a drink and a pie, but it’s also offering plenty of items at the other end of the price scale. Its honey-barbecue glazed chicken tenders are more than $6 without any drinks or sides, and the new Bacon Smokehouse Quarter Pounder meal runs nearly $9 in Chicago.

Fast-food menu prices are now approaching those of fancier, more modern chains that like to tout farm-to-table ingredients. In 2012, a hamburger from a fast-casual joint like Habit Burger or Shake Shack Inc. used to be nearly 30 percent pricier than fast food. But the difference has narrowed to less than 8 percent as median fast-food burger prices creep higher faster.

Franchisees have been bumping up prices to maintain margins as wages and worker expenses rise, according to Omair Sharif, senior U.S. economist at Societe Generale.

“There’s more price competition at the fast-food chains versus what you’d expect to see at a full-service restaurant,” he said.

Before the last decade, all food prices — whether at the grocery store or in a restaurant — increased at a similar rate. But since about 2009, the growth patterns have diverged, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. That’s because eatery prices are mostly made up of labor and rent, unlike at supermarkets. Lower farm and commodity food costs have helped keep prices down at grocery stores, but dining establishments have felt less of that benefit.

As cooking at home gets more attractive, visits to U.S. fast-food restaurants have been declining, MillerPulse data show. The big chains bemoan the battle for diners, and in turn, resort to steep discounts — at least for a handful of items they figure will get customers in the door.

“It’s a market-share fight,” McDonald’s Chief Executive Officer Steve Easterbrook said on an October call. “I don’t see many people, many out there in our sector, who are actually growing traffic at all.”

Dominic Flis, who owns 23 Burger Kings in Arkansas, says he’s probably going to raise menu prices on some items in January to help offset all the discounts. He’s also facing a 75-cent hike in the state’s minimum wage. Flis says he can only control the price of certain items, so he’ll likely target fries, drinks and combo meals for the planned nickel and dime bumps.

“If the discounting continues, I believe all of us will have a hard time,” he said.

—With assistance from Scott Lanman.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.

This article was written by Leslie Patton from Bloomberg and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to [email protected].